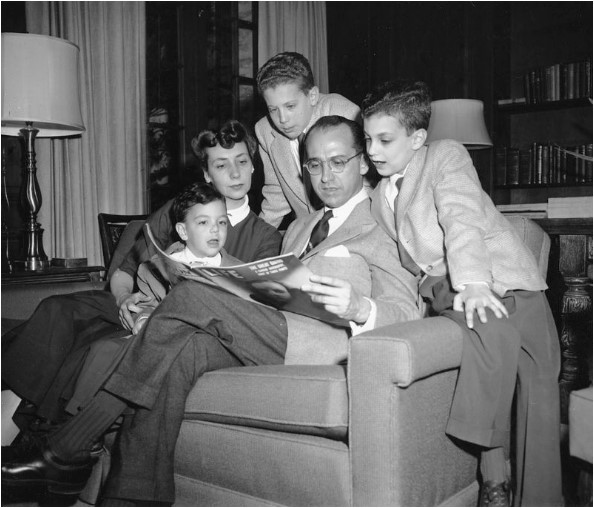

In this April 1955 photo, Dr. Jonas Salk reads Life magazine with his wife, Donna, and three boys. From left are Jonathan, 5, Peter, 11, and Darrell, 8.(AP)

Peter Salk still remembers the trepidation he felt when his father came home from work one day in May 1953 and promptly began boiling a set of needles and syringes on the kitchen stove.

With several years of research and promising results in monkeys fueling high hopes, Dr. Jonas Salk had brought from his lab at the University of Pittsburgh a still-experimental vaccine candidate to their Pine home. His family would become among the first humans in the world to test a shot against the mysterious polio virus crippling and killing children.

“I’m sure that my father told us [the importance of] what was happening,” said Dr. Peter Salk, 76, a University of Pittsburgh professor of infectious diseases and microbiology and president of the Jonas Salk Legacy Foundation, speaking by phone from his California home. “I … was just not happy at the notion of having another shot.”

Peter Salk was 9 years old. He didn’t have a sense of the medical history that he and his family were making, nor the millions of lives that would benefit.

All he knew was that, like many kids his age, he hated needles — so much that he’d previously crouched and hid behind the kitchen wastebasket to avoid getting one.

Standing beside his two brothers, he braced for the injection. Two weeks later, they received a second dose while photographed to generate publicity for the March of Dimes, which was pumping millions of dollars into polio research.

“The point of that was to demonstrate my father’s confidence in the vaccine,” Salk said. “But … it was also, from my father’s side and my mother’s side, ‘Let’s get these kids protected.’”

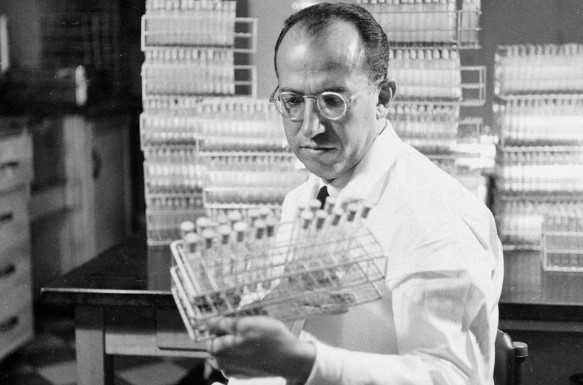

In this Oct. 7, 1954, photo, Dr. Jonas Salk, developer of the polio vaccine, holds a rack of test tubes in his lab in Pittsburgh.(AP)

Last month marked the 66th anniversary of the day when the first inoculations began on nearly 2 million children who received Salk’s vaccine candidate in 1954. By 1955, the pivotal public health experiment was deemed a success, with the vaccine proving to be safe, potent and 90% effective in thwarting polio.

The achievement put Pittsburgh on the global map as a leader in cutting-edge medical research and set the stage for decades of investments and advancements in Pitt’s vaccine research capabilities. As the nation confronts the covid-19 pandemic, Pittsburgh scientists have joined the global race to stop the spread of yet another disease horrifying the world.

Much has changed in terms of medicine, technology and FDA regulations around vaccine development since Salk’s quest in the 1950s. Scientists today, for instance, typically are not allowed to start trying out their experiments on their own kids.

“In 2020, it’s much harder to do that kind of self-experimentation, although it does occur,” Adalja said. “There are a lot of concerns that the FDA would have regarding human research subjects. Was there informed consent? Are they part of a proper trial? All of that would be something that would probably not happen as easily as it could in the 1950s.”

Scientists also have so much more technology and methods available, with the COVID-19 genome sequence getting mapped within mere weeks of the first samples studied in early January.

Read the full article from the Pennsylvania newspaper The Morning Call